In a low brick building on Eighth Street, with business offices in the front and a line of printing presses in the back that would shake the walls when they ran, The Sentinel-Ledger of the 1990s continued to operate much as it had for more than a century.

Each week – twice weekly in the summer – a tiny newsroom crew filled those gray broadsheet pages with details of parades, flower shows and elections, homicides and house fires, high school sports and City Council deliberations.

The office itself was close to chaotic, with stacks of newspaper surrounding each desk and a pervasive smell of stale coffee and fresh ink.

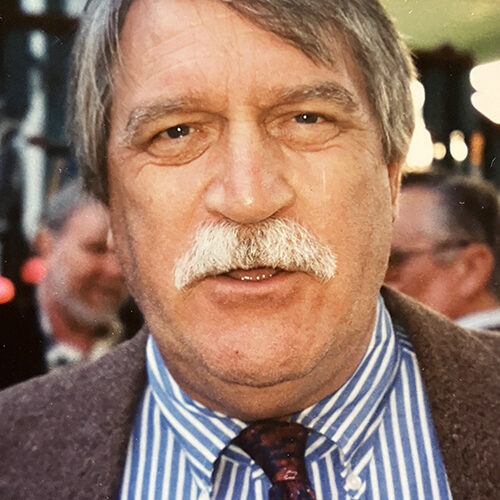

In a swiveling desk chair that looked like it dated from the 1930s sat John H. Andrus II, the editor who gave me my first newspaper job.

At the time, it seemed as though he was formed there, in that dim office, reading copy, asking questions and trying to keep the whole thing running. He was a bundle of contradictions, profoundly disorganized and perpetually a little behind schedule even as he cajoled his late and disorganized reporters to file earlier, to plan ahead and to be better prepared.

As reporters, we would diligently cover meetings, uncover scandals, corner politicians and pry loose details of small-town crimes from the trivial to the horrific.

There were always more details to ask about. What kind of gun? Where was he stabbed? How old was she? How much weed did he have when the cops searched him? Where did the fire start? What was the dog’s name? And always, always, how much will this cost?

Invariably, we’d write most of the paper the morning of deadline, scrambling to finish an A1 story while the sports section began to roll off the press. Each week, John would plead for us to file earlier.

John would not countenance any suggestion that we were just a local weekly, that what we did might not matter as much as the writers on the big metro dailies or the national media. We were writing for the community, we were writing for the world and we were writing for history.

When people of the future wanted to know what was happening in Ocean City and the surrounding communities, John said, they would look to the issues of The Sentinel. He had a point. The newspaper’s morgue, or archive, stood packed floor to ceiling with books of back issues dating to before the Sindia ran aground at the turn of the 20th century. World War II rolled out week by week in those yellowed bound pages, at least as seen from Ocean City.

John lived around the corner from the office, in a second-floor apartment that at times seemed almost impossibly cluttered. We’d sit on the outside deck and drink beer or red wine or whiskey and watch the old draw bridge at Ninth Street go up and down, snarling the summer traffic.

Aside from the occasional trip to The Waterfront in Somers Point or to the supermarket for supplies, he seemed to rarely stray from the path between the apartment and the office, spending long, long hours bathed in the light of a computer screen that even then seemed obsolete.

Still, he seemed to know everyone and everything. He remembered every election and every trial that later put the successful candidate in jail. He knew who to call for answers to those endless questions, and the meaning of the police codes that came over the crackling radio scanner in the corner.

More importantly, he understood what made a good story, and what separated a good story from a great one. He pushed too hard almost all the time, especially for a group of misfits who worked 60 hours on a slow week and could have made more money tossing pizza. But most of the folks who worked with him remember those lessons in journalism, hearing the questions he would inevitably ask when reading the story, and learning to ask them ourselves before we wrote it.

He worked for The Press, helped launch The Herald and after the Sentinel went on to the Reminder in Cumberland County. But in my mind, he was always the editor of the Sentinel, in an ancient desk chair in a cave built of piled back issues and municipal budgets.

John, who was born Oct. 24, 1940, died on Wednesday morning, May 15, 2024. He had been sick for a while, and his life slipped away from him piece by piece, although he remained fully himself as his new physical limitations shrank his world.

His longtime love Natalie Reed was there with him, day after day, with his son John and daughter Kris coming to offer the comfort of their presence. Perhaps fittingly, or maybe not, my last visit we shared a Guiness. He had trouble holding the glass steady in his hospital bed in the sunny front room and his voice was thin and high and quiet, but he seemed to enjoy each long sip.

Anyway, I hope so.

This isn’t hagiography, or at least it shouldn’t be, not for a man who spent his life working in facts and the craft of getting them to people. John had plenty of faults and could be in turns endearing and infuriating. He was stingy with affection and compliments, always assuming people knew how he felt without the messy business of expressing it.

Even 30 years ago, we would joke about the dire state of the news industry. We worked in a tiny outpost of 19th century technology as the 21st came charging in. Tight budgets were constantly getting tighter, year after year after year, and each year, fewer reporters remained to keep an eye on the public’s business.

No one reading this online or in print has failed to notice the threats to journalism, not just financial, but existential. A major party candidate, and a significant part of his party, routinely derides the news media as hopelessly biased, even as reporters wrestle with how to fairly cover those assertions while remaining faithful to their imperative to tell the truth without fear or favor.

An increasing number of people have trouble differentiating between news, opinion and propaganda, while bad actors continuously seek to further blur those lines, and it seems like more and more of the online cacophony denies the possibility of apprehending objective reality at all.

Still, the work goes on. The Sentinel prints each week, as do other local weeklies and dailies, and locally focused websites let the community know what is happening around them. Reporters still ask their inconvenient questions of powerful people. As many problems as the diffuse new media landscape presents, it also offers extraordinary new options for reporting, from how information can be gathered to how to tell the story.

So here are a few of those lessons John Andrus imparted to so many young reporters:

Reporters serve the readers. Not the editor or the publisher, not the sources, certainly not the advertisers, no matter how much they may insist otherwise.

Check the facts. If someone tells you something, report it and attribute it, but wherever possible, find out what else is being said, and what the source may have left out. Confirm, confirm, confirm.

Check rumors. Rumors are constant in a small town and should not be relied upon. But they are also very often accurate. Or at least include a core of truth that no one is going to admit unless you keep digging.

Get the document. When a court filing, a monthly activity report, an election finance statement, almost anything becomes public, get a copy and read it. Compare it to what was said at the meeting. Sometimes they are two very different things.

Politicians must answer questions. I remember one of the few times I saw John get visibly angry on the job, when an elected official dodged call after call. My rookie instinct was that he was just too important and busy to bother. John’s was that he was ducking a fundamental responsibility and should be held accountable.

Get their photo. When you talk to anyone, take a picture. For those who get elected, get two, one smiling and one not, to use when they get reelected or arrested. I think he was only half joking.

Everyone has a story. Most people get their names in the paper three times: When they get born, married, and for the obituary, or as John would put it, “Hatched, matched and dispatched.” Rather than quote another politician, talk to someone who hasn’t been asked before, and keep an ear out for the stories people tell each other but which do not get in print. On the other side, when reporting on a tragedy, keep in mind the humanity of those involved. Write it up with the understanding that the subject’s family will likely read it before you get clever with a headline about a fatal accident or drowning.

Write it up. Facts don’t do anybody any good in your notebook. This also serves to mark a place and time, so that when an elected official says, for instance, that there is no indication at all of any missing money, you have the story to point to a few months later when the grand jury hands down indictments.

Keep it simple. Direct language is always best, in the active tense wherever possible. But if an obscure or complex word is the exactly right one, use it. Don’t be afraid to occasionally send them to the dictionary. And don’t be afraid to use the dictionary yourself when you think you have that perfect word, to ensure it means what you think it means.

There were more. A lot more, from the pragmatic to the esoteric. But the main one, taught by example as often as stated, is that community journalism matters. It doesn’t pay well, the work is often disdained or actively mocked, but it is significant to democracy, to history and to understanding the world.

Tell the story. The story matters.

Bill Barlow is an Ocean City resident and longtime newspaper reporter who began his career at the Sentinel-Ledger.