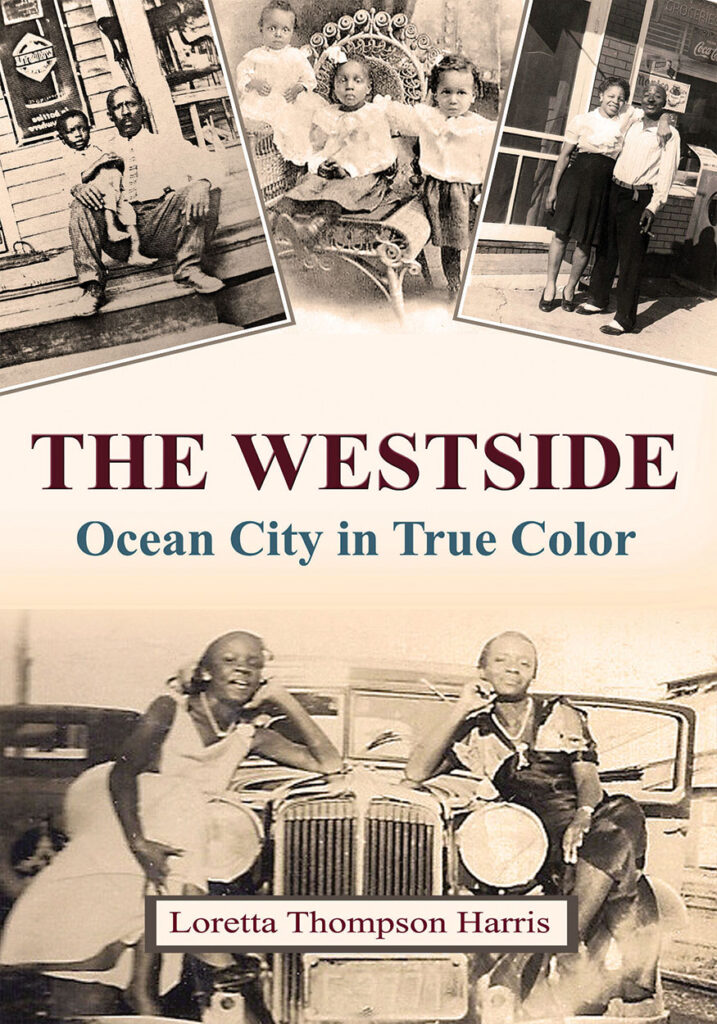

OCEAN CITY — For someone who just published the first of a series of books on the history of people of color in Ocean City, author Loretta Thompson Harris wasn’t partial to studying history back in high school.

“It’s really hard to believe,” Harris acknowledged during an interview last week ahead of a planned signing of her new book, “The Westside: Ocean City in True Color.”

She loved everything at Ocean City High School (Class of 1963), except history, which, she notes, is ironic.

“In school the things they taught us in history didn’t interest me, basically because they weren’t about me,” she said. With a laugh, she added, “It was memorizing a lot of dates and a lot of European kings and queens.

“About the only thing they taught us in school about people of color was about Indians. I always felt like Indians got a bad deal. My grandmother on my father’s side is Native American.”

The overall interest in history changed later in life when she began researching her family background. She discovered her great-grandfather founded a church down the block from where she grew up in Ocean City and learned about a connection to James Still, the “Black Doctor of the Pines” and brother to abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor William Still.

Now Harris has profiles of 80,000 people, one book published, two more in the works and possibly a fourth … if she has time.

“We never talked about our family history. Never ever,” the fourth-generation Ocean City native said. “One day I was sitting on the steps outside of my dad’s house and had just gotten a letter from a relative on my mother’s side from Florida.” As she was sharing details from the letter, her father said, “Well you know your great-grandfather was one of the founders of that church. He pointed to the end of the block at St. James AME Church. I was shocked.

“I never knew my great-grandfather lived in Ocean City,” she said. He had a baggage-handling company at one of the city’s long-since-gone train stations, on Haven Avenue, with an exclusive for handling the baggage.

She jotted that information down on the envelope of that letter, a memento she has kept.

Later on, she was again sitting outside talking to her father and he told her they were related to “the Black Doctor of the Tall Pines. His name is James Still. Others called him the Black Doctor of the Pines. Dad called him the Black Doctor of the Tall Pines. I knew nothing about him. I had never heard of this man.”

Her father told her to go see her aunt because she had a pamphlet on James Still. When she got there, the aunt didn’t have a pamphlet; she pulled out the family Bible.

“I didn’t find this Black doctor in there, but I saw a host of names I hadn’t heard of. They were all family members,” Harris said.

She learned James Still was an herbal doctor who taught himself medicine and lived in the Medford area, which is where the “tall pines” reference came from. She also learned he was the brother of William Still.

The Still family was large. “I found out that the first Black to come to Ocean City was a Still,” she said.

“Our connection to the Still family is rather remote. My father said we were related, but to me it’s rather remote.”

Jacob Still, she noted, opened the first saltwater taffy shop in Ocean City. His business was in the Brower Building at Eighth Street and the boardwalk.

After her conversation with her aunt, she decided her contribution to the family history would be to pick one person, do the research and give the information to her aunt.

Little did she know what she was starting.

“I picked John Brooks Thompson because I liked the name. It turned out he was this great-grandfather who had come here right after turn of century, in 1900, and had this business handling baggage at the train station. He lived right at Seventh and West Avenue. He died in the 1920s so I never knew him but his house was only a block away,” Harris said.

John Brooks Thompson was originally from Salem City in Salem County and his wife, her great-grandmother, also was from Salem County.

She was able to trace the line back to her great-great-grandfather who was born about 1805 and died in 1892 back in Salem. Harris said she tries to take back every family line into the 1700s, but couldn’t quite get there with her great-grandfather.

This was supposed to be her one contribution, she said, “but I was hooked.”

“How can your great-grandfather live a block away and I didn’t know it? And to boot was one of the founders of my father’s church?”

She now lives in Upper Township and she has to drive down a little dirt road to get there that goes by an old cemetery.

“For years I had been passing the cemetery where (my great-grandfather) was buried without ever knowing it,” she said. “I think that’s enough to get you hooked on the story. And learning about my family. In the process I was learning about other families and I had to spread out to get the big picture.”

Harris has been doing research on her family for 30 years or so and as she did it, she began to get calls from other people asking her to help with their family history.

She added their histories to her tree on ancestry.com, a gift from her daughters, because the computer helps her research.

“I found so many people did not know their family history either. They knew even less than I did and when I shared the information, there is always a lot of emotion and a lot of tears. They were so happy and relieved to know who they were and how they fit in this world. I still help a lot of people because it’s really rewarding.”

“As I attach people to my family tree, it becomes a community tree,” she added with a laugh. “I have profiles on over 80,000 people.”

She said the large number of people isn’t cumbersome because she does profiles one a time, some long, some short. She is now known as an Ancestry Ace.

The company asked her to split up the tree because it was so big, but she decided not to because then she would have too many trees. Her tree used to be public, but she made it private because she got so many requests she couldn’t get to her own work. She also said people were copying the information but not taking the time to verify it. Just because she puts something down in her notes, it might not be correct, Harris explained.

She does volunteer information if she gets messaged.

Now she has “volumes and volumes” of it.

The Ocean City Historical Museum asked her to join its board because it realized it was lacking history about the African-American population in the resort. Harris agreed with the proviso she could use the museum’s resources.

“The deal was, I’ll help you if you help me. They have information here that’s good. You start tying it all together. That’s how I started work with museum. They showed interest in getting some African-American history here in the city. I thought that was a good thing.”

– STORY By DAVID NAHAN/Sentinel staff