OCEAN CITY — Shiho (Kikuzaki) Burke’s peace activism is personal. Her family was in Hiroshima when the U.S. dropped the first nuclear weapon on the city Aug. 6, 1945 to end World War II.

She got involved with director Hideaki Ito’s film “Silent Fallout: Baby Teeth Speak” because she share’s the director’s vision.

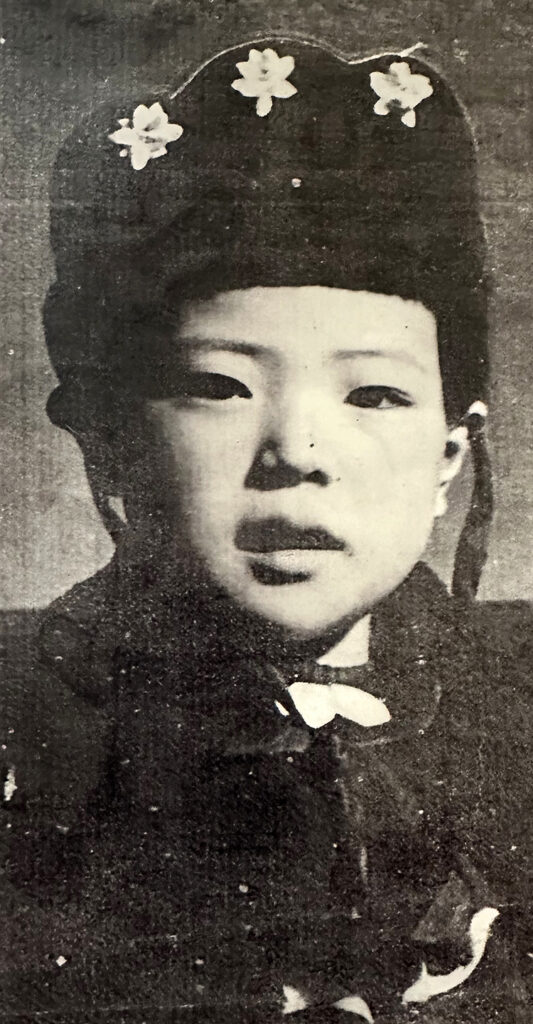

Shiho is the only daughter of Mizuha (Takama) Kikuzaki, who was a little girl in a school 1.1 kilometers from ground zero. That child climbed out of the rubble after the devastating explosion that leveled much of the city, but she developed white blood cell disorders.

As an adult, Mizuha had four miscarriages and one stillbirth when she was eight months’ pregnant. She gave birth to Shiho when she was 40 years old, despite being strongly advised against it.

Because there wasn’t such a thing as ultrasounds 50 years ago to check the condition of the fetus, doctors recommended terminating the last pregnancy, but her mother refused. Fortunately she found a good obstetrician who told her he knew even if she had a child with a disability, she would care for her.

“He was the only one who supported her decision,” Shiho said. “Her siblings didn’t want her to have me because she might lose her life.” Her mother was determined.

“I always say to my kids, if she didn’t make that decision, they wouldn’t be here,” she added, her eyes welling up. “Thankfully she did (have me) and was alive.”

In spite of her health problems, her mother lived until 2017, when she died at age 84. She was told she was terminal at age 27.

“I want them always to remember what happened,” she said of her children knowing the family history and the bombing of Hiroshima and its aftermath. “That’s why I want everyone to remember what happened.”

Her mother’s health issues weren’t the only family misfortune.

Her grandfather, Hidemitu Takama, died in October 1945 because of radiation poisoning from the “black rain” that fell on him while trying to help others after the bombing. He was a government official.

Shiho’s grandmother, Tadako Takama, was at home with daughter Futaba when the bomb hit. Although her grandmother was severely injured and needed reconstructive surgeries, she survived. Futaba didn’t suffer any serious immediate physical injuries but would die of ovarian cancer in her 40s.

Shiho noted families didn’t want their sons marrying girls from Hiroshima, but Futaba did marry. However, she had made the choice not to have children after seeing all the children born with disabilities after the war.

Shiho’s two uncles, the other two siblings in the family, were teenagers working at a factory making plane parts as part of the war effort because they weren’t allowed to go to school. Gyoji was 13, Kunihiro was 15. They were both injured in the blast. Kunihiro was left in a wheelchair.

“In Japan, being the oldest means a lot. It means taking care of your family,” Shiho said. “After his father passed, he felt responsible, but he was in a wheelchair. He had to end his life because of all the pressures and depression because he felt like he was a burden to his family,” Shiho said.

Her uncle committed suicide around age 20. Gyoji ended up working in the black market after the war.

“It was a struggle for a lot of people after the war in Hiroshima and throughout Japan,” Shiho said.

Her own mother wasn’t supposed to be in Hiroshima when the bomb hit. She and other children her age had been evacuated to the countryside to protect them, but she didn’t want to be away from her family so she spent two days walking home.

“And of course she got bombed,” Shiho said. “She went to school that day. All of a sudden the building collapsed and she couldn’t see anything. Then she saw some light and climbed out. It wasn’t her time. That’s what she always said.”

“The sad thing is they had such a happy family, but because of the bomb everybody’s life was ruined. The war just takes everything away from people. Peace. Sanity. Family.

“I don’t know why after all those years we haven’t learned and keep fighting. We don’t want our children to fight old men’s wars,” she said, but noted the many conflicts around the globe at present and the continued proliferation of nuclear weapons.

“It’s crazy what’s going on in this world and they never (care) how civilians are affected.”

Shiho kept an official Japanese government booklet that documented how far her mother was from the epicenter of the atomic detonation. That distance – 1.1 kilometers –helped determine what the government did to support and care for her postwar.

Her grandfather came from a Buddhist family and her grandmother came from a Christian family. Shiho’s mother was raised by her maternal uncle, a Christian theologist and missionary who spent three years at Duke University in North Carolina and then in Heidelberg, Germany. Her mother was born in Japan but spent her first years in Germany with her uncle.

When her mom was still a child, her uncle died of cancer in the early 1940s, which is why she went back to Japan to her biological parents. She first lived in Osaka but then went to Hiroshima. Tadako lost her adoptive father and then lost her actual father to the atomic bomb in Hiroshima. (Shiho’s own father lived until he was 65, before dying from the effects of cancer and a stroke.)

Shiho went to the same schools as her grandmother, Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior High and High School, and her grandmother also attended Hiroshima Jogakuin College. They were founded in 1886-87 by the Rev. Teikichi Sunamoto and a Christian missionary from the United States. Shiho then went to the U.S. as an exchange student for the rest of high school at Norfolk Christian High School. She attended George Washington University in D.C., Okayama University in Japan and the City University of New York Hiroshima branch. Family and marriage later brought her to Ocean City. She later moved to Somers Point. She has been a translator, art dealer and real estate broker.

Shiho’s youngest son, James, graduates this June from Ocean City High School. Her daughters Mary and Grace also graduated from OCHS. Grace just graduated from the Albert Dorman Honors College at the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT). Shiho now lives in Somers Point.

Shiho has been a peace activist around the world. Those family experiences inform her activism against nuclear proliferation and nuclear power.

She got involved with director Hideaki Ito’s film as an interpreter for Ocean City’s Joseph Mangano, who was being interviewed by the director, and since then has been helping support the film.

She explained the director’s passion is the same as hers: that Hiroshima and Nagasaki shouldn’t just be something in the history books.

“It is very close to us, no matter where you live, you were exposed to radioactive materials. There have been so many (nuclear tests) … everywhere. And the government doesn’t really tell us the truth ever,” Shiho said. “I think if everyone knew the truth, they probably wouldn’t have dropped those bombs on civilians in Japan.”

The activist is concerned with continued nuclear proliferation and nuclear power because plant emissions contain the same deadly materials.

She was upset how the Japanese government handled the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant that was damaged and released radioactive materials after being hit by the massive, deadly tsunami in March 2011. She went back to Hiroshima then to bring her mother to the U.S.

“She was already exposed once (during the war) and I didn’t want her exposed twice,” she said, even though she was living far from the damaged nuclear plant.

“I would really like to see disarmament of all the nuclear weapons. It’s not an easy goal to reach but I feel we shouldn’t be taking the risks anymore. We can’t change the mistakes we made. We can only change the future by learning from the mistakes and not repeating ourselves again and again and again.”

To schedule a screening of “Silent Fallout,” a film meant for the U.S. audience, send a message to her at burkeshiho@gmail.com or email sachi.com@goldensachi.com.

Director Ito will be in the U.S. from July 10 through Aug. 20. They have already set up screenings in multiple states.

– STORY by DAVID NAHAN/Sentinel staff

– PHOTOS courtesy of Shiho (Kikuzaki) Burke