‘Minister of history,’ founder of S.J. museum, talks of origin, growth of the Black Church

OCEAN CITY — Ralph E. Hunter Sr. comes from a family with three generations of ministers, but decided long ago that his path is preaching about the region’s African American history.

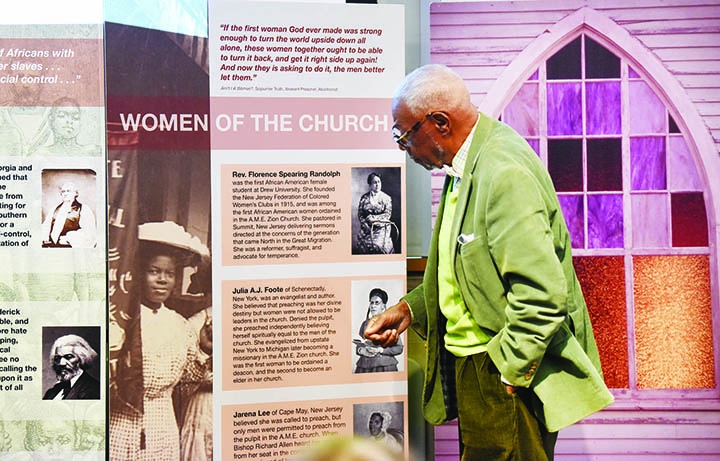

Hunter, founder and president of the African American Heritage Museum of Southern New Jersey, brought one of the museum’s traveling exhibits to the Ocean City Historical Museum on Saturday afternoon.

The exhibit, “This Little Light of Mine: The Black Church,” was set up in the Ocean City Free Public Library’s lecture hall as part of its Black History Month exhibit. Hunter entertained and informed a sizable crowd there with his lively speaking style, punctuated with humorous anecdotes but with serious intent about how the Black church rose out of slavery, the discrimination that existed in the area that affected life and generational wealth, but also some of the successes that arose in spite of it.

Often asked why he did not choose the ministry, Hunter explains that he loves history and “became the minister of history in his family.”

Hunter came to Atlantic City in the 1950s and fell in love because he saw a thriving African-American community with people who looked like him owning businesses.

“When I got off the bus for the first time … I fell in love. I couldn’t believe I saw police officers who looked like me,” he said, and restaurants filled with people like him.

He talked about Sara Spencer Washington, one of the nation’s first Black millionaires, an entrepreneur who founded Apex News and Hair Co. in the resort, a beauty products school and company that would employ 3,500 people.

Because African Americans were not permitted on white golf courses, and visiting celebrities such as boxer Joe Louis wanted to play golf, she had a nine-hole course built on her farm in Pomona, the Apex Country Club.

Juxtaposed with that success, however, Hunter pointed out that Atlantic City was two separate cities — the north side where the African American population lived and the south side with the boardwalk.

Hunter explained the impact on the African American residents of redlining — the demarcation of where they could rent and own property. That factors into generational wealth because of the lower values of properties in certain areas.

As an example, Hunter said he had a house built on the north side of Atlantic City in 1961 and a friend had the exact same house built in Ventnor. His house is now worth $100,000 but his friend’s is valued at $700,000 — a vast difference when trying to pass on property to the next generation or sell to fund retirement.

Hunter became a collector of African-American memorabilia, but he also was a donor. His grandfather had a storefront church in Memphis, Tenn., and his father would stand outside blowing his trumpet to attract people to come inside the church.

Seven years ago, Hunter said, he got a call from a curator with the Smithsonian Institution asking about the trumpet. It was in Hunter’s collection but is now in the national museum’s collection next to Dizzy Gillespie’s horn.

Hunter began his own collection decades ago and related the story of how he first started collecting after he sold his own business. When he came to an antiques store in North Carolina, he inquired if there were any Black or African American items available, but the clerk told him the owner didn’t want the one item available displayed.

He said he would buy it, sight unseen, then discovered it was a copy of the book “The Story of Little Black Sambo,” which held bad memories for him because his teacher would read that to his class as a child.

He decided his mission would be to buy up every copy of that book and burn them because of the stereotypes pictured, but then he decided to read it and realized it was about a boy in India. (The book was considered progressive in 1899 when published because it had black heroes, but problematic in the mid-20th century because of the style of the illustrations and names being used as racial slurs.)

“The moral of the story … that was the very first thing I purchased,” he said, and has since bought a copy of every edition by the author, Helen Bannerman. The museum’s collection notably includes items that portray African Americans in both flattering and unflattering lights.

There are two physical locations for the African American Heritage Museum of Southern New Jersey, one at the Noyes Arts Garage in Atlantic City and the other at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center in Newtonville, but as Saturday’s talk displayed, a key facet of the museum is its traveling exhibits that are brought to schools and other organizations.

This Little Light of Mine: The Black Church

Hunter brought the traveling exhibit on the Black Church to his talk. It goes into the history of the Black Church and its founding in the late 1700s after “The Great Walkout.” That was when African Americans, tired of being segregated at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, followed former slaves and lay ministers Richard Allen and Absalom Jones walking out of the church in protest.

In 1794, Allen would found the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Other independent denominations would follow.

Hunter said he understood why they walked out and that it was “kind of like walking off of a plantation.” If you don’t like what the master is doing, the way you’re being treated, start your own denomination.

He noted a woman in Cape May was the first to preach from the pulpit even though women had been forbidden from that role — after she displayed more knowledge of the Bible than an assistant pastor who was speaking. According to the exhibit, after Allen heard her, Jarena Lee of Cape May was the first woman allowed to preach in the A.M.E. church.

Hunter explained there wouldn’t be a Black Church without slavery. The exhibit shows how Christianity had been used as a tool of social control among slave owners, and that white ministers would tell slaves how thankful they should be to God for being brought from the shores of Africa and allowed to hear the gospel.

According to the exhibit, Frederick Douglas, a former slave who became a national leader of the abolitionist movement, said of Christianity, “I love the pure, peaceable and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land … .”

There was a hunger for Christianity, however, among the slaves, who sought the compassion and morality of the Christian faith, ideals that continue in the Black Church.

The exhibit notes other women of the church, early congregations in New Jersey such as Woolrich (1799), Elsinboro (1800), Swainton (1840), Cape May (1854) and multiple in Atlantic City.

The exhibit also notes that origins of Gospel music during the 1930s Great Migration and how during the 1963 March on Washington, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, it opened with the national anthem sung by Marian Anderson, a famous African American singer who was refused permission to perform at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., in 1939 by the Daughters of the American Revolution. (She sang that year instead on a platform at the Lincoln Memorial.)

Although New Jersey was a free state, there were plantations and slaves in southern New Jersey, Hunter said.

He said his museum has the tool chest of the last freed person in New Jersey, a woman named Lucy who was a carpenter. He said a researcher for the museum had to go through five generations — starting with the slave-owners — to track down the chest that is now on display.

Hunter said in his first five years of collecting, he amassed some 3,000 items. Among the museum’s collections now are everything Jackie Robinson had as a rookie baseball player including his glove and his bat.

Among the museum’s traveling exhibits are “Jackie Robinson: Stealing Home”; “A Time For Change” about the 1960s and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party trying to seat their delegates at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City; and “Talking About HERstory,” stories about African American women through history.

During a question and answer session after his talk, Hunter and members of the audience discussed how segregation continued here in southern New Jersey, with segregated beaches enduring in Atlantic City, Ocean City and Cape May, things that didn’t start changing until the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

He mentioned Chicken Bone Beach, how it was named by people who claimed they found chicken bones on the one beach African Americans were allowed on in segregated Atlantic City. Hunter pointed out how, as a historian, people wouldn’t find it funny were they attributing naming stereotypes related to Jews or Italians or Irish Americans in other island resort communities.

That is why he refers to that beach only as Missouri Avenue beach because all of the other Atlantic City beaches are named after streets.

During the Q&A it was noted that the old Ocean City High School had a swimming pool but Black students weren’t allowed to use it. After protesting, they finally were allowed in on Fridays after school … because the pool was cleaned Saturdays.

To learn more about Hunter, the museum and the traveling exhibits, go online at aahmsnj.org.

The museum at the Noyes Arts Garage, 2200 Fairmount Ave., Atlantic City, is open 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday. The Newtonville museum, 661 Jackson Road, is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.

By DAVID NAHAN/Sentinel staff